I expect (and kind of hope) that many people reading the title of this section will think, “Uh, I don’t need instruction about how to walk. I’ve been doing it all my life.”

I also expect (and definitely hope) that others will read the title and think, “Finally, the answer to my most burning question! I’ve been worried that I’m walking wrong.”

For those of you in the first group, let me ask you this: Do tribal women in Africa with water jugs balanced on their heads walk in the same way that Olympic race walkers do? And, do either of those people walk the way you do?

I’d bet that the answer you found for both of those questions is No.

That’s because walking isn’t just walking. There are ways of walking that are more or less effective, more or less efficient, more or less healthy and strong.

And if you accept that premise, that could put you in the second group.

Now, for those of you in the second group, I have what could seem like bad news. There is no one answer to “How do I walk.”

This article will not reveal the hidden secret of locomotion that only wisened Tibetan lamas from the Drepung monastery have taught to their senior disciples, or the geometrical relationships between your lower extremity joints that is optimal for effortless, pain-free walking, or the best footwear you can use for carrying a 200 pound pack on a 1,000 mile hike over broken glass.

It’ll actually do something better.

It’ll show you how to become your own best teacher and discover your own secrets for walking efficiently, enjoyably, and easily.

Before we can discuss walking, lets review of the premises behind, and arguments supporting barefoot running: Landing on your heel, especially with the ankle forward of the knee and the knee almost straight, sends shock through the joints — the ankle, the knee, the hip, and up the spine.

This isn’t good.

Running barefoot reduces the likelihood that you’ll land on your heel… because it hurts.

Landing on the forefoot or midfoot, with a bent knee and the ankle not front of the knee, reduces the force going through your joints, allowing you to use the muscles, ligaments, and tendons as natural springs and shock absorbers.

So, what does all this have to do with walking?

Well, the whole conversation about foot-strike rarely came up prior to the barefoot running boom. Now it’s practically dinner party conversation, where the barefoot gang looks down their noses in disgust at shoe-wearing heel-strikers. And the increase in the volume of the foot-strike conversation has led to another question, which probably nobody asked prior to the publication of Born To Run. This is a question I’m emailed almost daily, namely, “How should my foot strike when I walk?”

It sounds like a reasonable question.

If there is some optimal way for your foot to land when you run, there must be a “right” way for it to land when you walk, right?

Well, there’s debate among the barefoot running research community about whether a forefoot strike is better/worse than a midfoot strike, or whether foot strike is idiosyncratic and different for different runners. There’s even an argument about whether heel striking is as evil as as most barefoot runners take it to be.

How can this be?

Simple. Because heel strike is the effect of other aspects of your biomechanics, not the cause.

Think about it. The only way you can change how your foot lands on the ground is what you do with your ankle, your hip, and your knee.

To not land on your heel when you run, you probably need to bend your knee more than you usually do. But that alone could cause you to trip over your toes, so you also need to bend your hip a bit more. And then you may relax your ankle a little rather than pulling your toes towards your knee.

So “land on your forefoot” is really just a cue for “bend the hip and knee and relax the ankle,” but if you told someone to change their hip, knee and ankle joint angles, they’d be too confused to even take a step.

Well, it’s similar with walking. Where your foot lands isn’t the issue. How you move your foot through space is.

When you walk, your foot can land in one of three ways: touching the forefoot first, followed by the heel dropping to the ground; landing basically flat-footed, probably touching the midfoot first, or; touching/rolling over the heel… which is sort of still a flat-footed landing but with the heel contacting first.

Which one of these happens is a function of how fast/slow you’re walking, whether you’re walking up/down hill, and what kind of surface you’re on.

Really, there’s no need to worry about foot-strike. It’ll take care of itself… if you pay attention to this next thing.

First, you’ll want to be barefoot, or as close to barefoot as possible.

Why? Because there’s value in being able to articulate the foot and to letting the nerves in your feet actually feel the ground.

Many podiatrists recommend barefoot walking as a cure for plantar fasciitis. Many chiropractors and orthopedic physicians recommend barefoot walking to cure lower back pain.

Being barefoot can help with plantar fasciitis because, when you’re out of shoes, especially on uneven surfaces, you’ll use your feet in a way that “pre-loads” the plantar fascia, putting them in a strong position when you need them.

Being barefoot can help with lower back pain because… well let’s take a look at that one more closely.

Imagine standing on one leg.

If I asked you to start walking, most people would basically swing their free leg out in front of them and, at the right moment, push off the toes of the back leg to pivot over the front foot, which has landed on the heel way out in front of you.

You basically walk “behind your feet.” One interesting thing about walking behind your feet is that you’re never really off balance. We’ll come back to that idea in a moment.

Now, imagine being on one foot again. If I asked you to contract whatever muscle or muscles you can think of that would move you forward, which one(s) would you tighten. Remember I said “move you forward.” Falling forward doesn’t count, so the answer is not “ankle” (leaning) or “abs” (as in, bending forward until you fall).

The answer is the muscles that are referred to as the “prime movers” in our body: The glutes and hamstrings.

Tighten the glutes and hamstrings and you’ll actually MOVE forward.

And stronger glutes and hamstrings protect the lower back.

But after you tighten your glutes and hamstring you will eventually get off balance and fall on your face… unless… you put your other foot down to stop you.

And here’s where it gets cool.

If you simply place your foot down where it’ll stop you from falling (rather than swinging it out in front of you like you usually do), it’ll land closer to your center of mass, more flat-footed, with a slightly bent hip and knee, and with the now front leg in a biomechanically stronger position. You will have planted your foot.

If you repeat this — using your glutes and hips to move you forward, and placing your foot instead of swinging your leg forward — you’ll be supporting your lower back… and your knees, and your hips, and even your ankles.

Your foot-strike will take care of itself.

You’ll feel like you’re walking “on top of your feet” rather than behind them.

And this makes you stronger, whether you’re going for a stroll or carrying a 50 pound pack on a trail (which, by the way, will be easier because your engaged glutes and hamstrings support your lower back).

When think about staying on top of your feet, and using your glutes and hamstrings, you’ll naturally discover the easy and efficient ways to walk in any situation. You’ll understand it from the inside out, from your own experience, not from some guidebook about how many inches behind your knee you should have your ankle when you’re walking up a 10 degree incline in 50 degree weather on a Thursday.

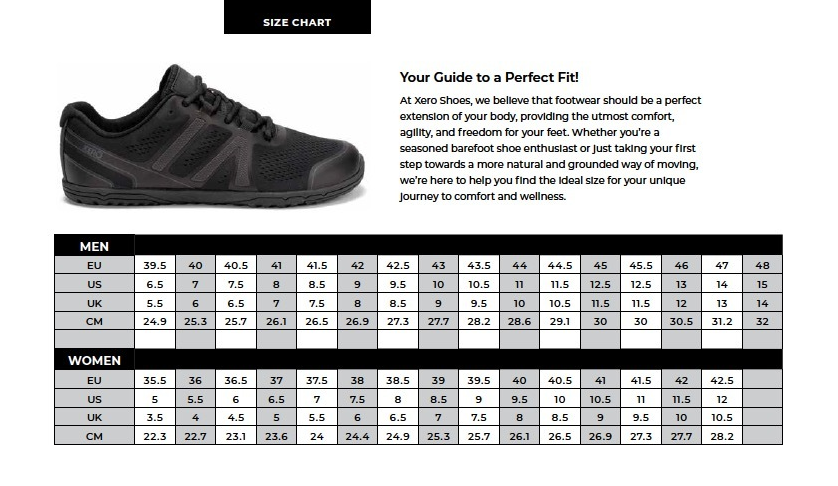

Combine this with feeling the world because you’re barefoot or in some truly minimalist footwear (be warned, most major shoe companies claim their product is “barefoot” when it’s about as close to barefoot as a pair of stilts), and I guarantee that your next walk or hike will be a revelation… and a lot of fun.